Seldom does civil society ask businesses to do more lobbying, but the energy transition seems to be a special case. On October 14, 2019, eleven major conservation groups, including WWF, the World Resources Institute and the Nature Conservancy published a full-page ad in the New York Times calling on American CEOs to “lead on climate policy” Financial institutions including The Church of England Pensions Board and Sweden’s AP7 made a similar call globally. One non-profit urges employees to voice their support for strong climate stances by their employers, another ranks firms’ “engagement” and “alignment” with supporting “science based policy” . In a 2024 Gallup-Bentley poll, 54% of those surveyed, and 63% of young people agree that “businesses, in general, should take a public stance on subjects that have to do with climate change”, a higher percentage than for any of the 13 other political topics measured. Some scholars agree.

At the same time, many worry about undue corporate influence on democracy in general. In the same Gallup Bentley poll, the proportion of Americans who agree that businesses “should take a public stance on current events” in general was at merely 38%, down from 48% in 2022. In last month’s CPR Hub Insight Amit Ron and Abraham Singer used pro-decarbonization climate change lobbying as an example of how even well-meaning businesses can undermine democracy through wielding their power via managerial fiat, even if it is backed by good intentions. They are not alone.

How can we square this vigorous support for pro-decarbonization climate lobbying from parts of civil society, investor groups, and the public with the general concerns that business already wields too much of the wrong sort of power in public affairs? Is this just special pleading for environmentalists’ pet projects? While I agree in general with much of Ron and Singer’s pathbreaking work on corporate political responsibility, below I present an argument that climate change does represent a special case that calls for more, rather than less political activity from business.

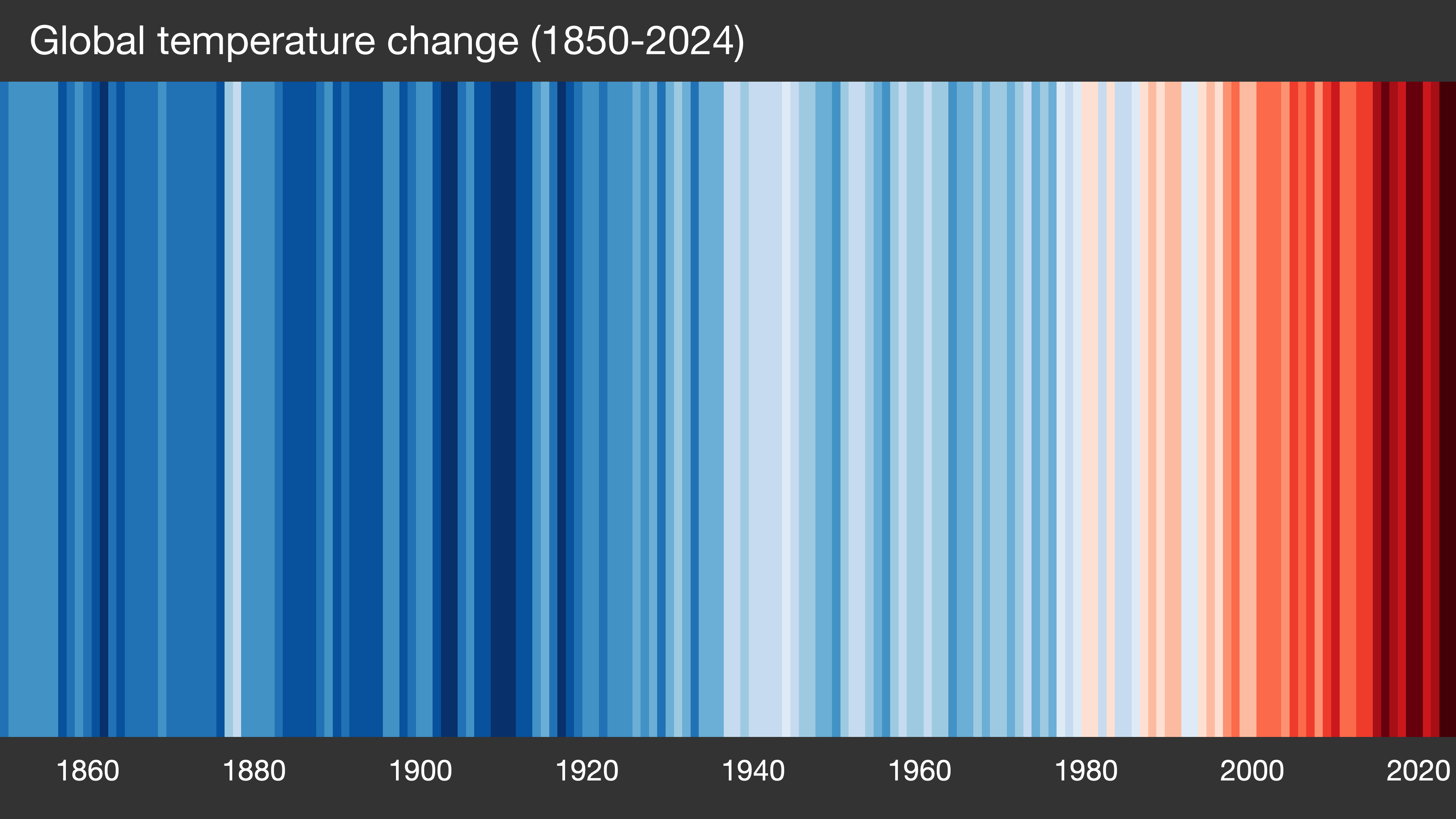

One sort of argument is that firms have permission to push swiftly and vigorously for decarbonization policy because it aims to correct a (massive) market failure, thus restoring what the Erb principles call “healthy market ‘rules of the game’”. Another sort of argument could focus on the urgent, possibly existential threat to civilisation that climate change might pose if worst-case scenarios unfold. But this is not just emergency logic: there is a story here about correcting an imbalance in influence.

Comments

Comment on this Insight